Scientists! Encrypt Your Mail if You Got Nothing to Hide

Up to now, I never bothered to encrypt my email as my attitude was that, as a scientist, I got nothing to hide. But in light of the recently installed science-deprived administration in the US, I’m starting to think that a healthy streak of paranoia wouldn’t harm after all.

Encrypting for the Sake of Transparency?

So here’s what I’ve been thinking about lately: Would encrypting email between scientists (and journalists) actually serve the scientific pursuit? Somewhat ironically, will it aid in scientific transparency by actually preventing censorship and politically motivated interference? I’m increasingly inclined to think so, but at the same time, I’m ridiculing myself for having these paranoid thoughts and I don’t want to be the one who’s scaremongering. Furthermore, I realize that admitting that you encrypt your email may invigorate conspiracy theories by those who are susceptible. However, under normal circumstances, using an encrypted or unecrypted email wouldn’t make any difference at all, and I simply see it as having an additional insurance against unauthorized access.

Better safe than sorry? Edward Snowden covers himself and laptop while typing his password.

Source: Still from Citizenfour (2014)

Your email may be deliberately taken out of proportions

The prime example of emails being deliberately misinterpreted is the Climate Gate Controversy. Where an email server of the Climate Research Unit at the university of East Anglia was hacked in 2009 and more than thousand of unencrypted emails were stolen. An email where Phil Jones mentions the use of a “trick” of Michael Mann to “hide the decline” (in temperature) was exposed in the media as ‘proof’ that climate scientists were deliberately misleading the public. However, a closer look revealed that it referred to a method to remove a spurious trend in tree-ring temperature reconstruction in favour of more accurate thermometer data, a common and scientifically accepted practice. And although subsequent investigations cleared the scientists of data manipulation and left the science intact, these allegations were harmful to (climate) science, and resulted in serious personal threats to the scientists. I can only imagine how frustrating and time consuming it must have been to rebute such claims.

Considering the amount of emails we send today, it’s probably quite easy to find quotes in our inbox which could be falsely interpreted by people lacking context. It therefore seems fair to lock/encrypt your email, to make sure only the recipients get to read them. Sure, if some emails need to be shared for the sake of transparency, one could decide to that on a case by case basis. But letting hackers and governments frenzy at ones inbox is outrageous and counterproductive. Failing to encrypt your email, opens the door to unauthorized people nosing through your email, which can have disastrous consequences, ask Hillary Clinton.

Staying ahead of the Trump administration

The installment of anti-science cabinet members of the Trump administration and the actions it has taken suggest rough times ahead for US and international science. The possibility of the new administration to censor science in order to push their conflicting policies, seems to become more realistic by the day, and fears that it would hurt the transparency of science don’t seem so farfetched anymore. Already, the new administration attempted to get a list of employees working on climate-related issues at the Department of Energy. What would they have done with the people on this list? Check their email? Furthermore, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), essentially responsible for implementing the Paris Climate Agreement, was ordered to have its climate section removed from its website. The website is intended to inform the general public about how climate change has affected and will likely affect the US, and outlines the possibilities for taking actions. The desire of the administration to take out this site essentially sends out the message that it doesn’t want the public to be informed about science.

So will this administration go as far as to start to monitor the inboxes of scientists? And, on the basis of that information, will they try to prevent scientific research from being published which go against their policies and ramp up gagging orders? I sincerely hope not, but I think it is in the best interest of science to keep ahead and let this administration know of scientific findings after being published out in the open. Encrypting your email when you speak to colleagues, journalists and press outlets, is a powerful way to aid this process. Media outlets such as the Guardian are seeing the importance of this and actually provide guideslines to contact them in safe ways, but among scientists, encrypting email still seems to be a remote concept.

So how does email encryption work?

Most of the time, when an email program (outlook, thunderbird, etc..) contacts the email server the transport over the internet will be encrypted via a secure protocol (e.g. TLS). Although most email-servers will drop the security layer when either sender or receiver does not support it, it will work for most modern email-programs and browsers, ensuring that intercepted emails can not be decrypted without disproportionate efforts. Generally however, your inbox will still be stored unencrypted at the email server, and may therefore be easily read when the server is compromised.

Use the public key for encrypting and the secret key for decrypting

Source: Wikimedia commons

A few email providers allow users to store encrypted inboxes on their servers. For example, Protonmail, designed by former CERN scientists offers such services as well as the Berlin based company posteo. Most of the time however you can’t choose your email provider for work related emailing, which means that you can’t control how your inbox is stored on its servers.

However, you can in fact, choose to store encrypted messages in your unencrypted inbox. For this to work, you can use the open source public key cryptography implementation of PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) confusingly abbreviated as GPG (GNU Privacy Guard). At the end of this post a few helpful links will be provided in order to allow you to set up email encryption on your devices of choice.

GPG is a so called assymetric encryption implementation. During its setup the user creates a encryption key-pair which contains a public part and a private (or secret) part. The idea is that everybody who’s got the public key is able to encrypt a message and send it to you. However, only the owner of the secret key is able to decrypt the message, not even the sender. Mathematically, the principle relies on the theory that it’s easy to multiply 2 (very large) prime numbers, but it is computationally very hard to recover those primes if only the product is available. If some genius mathematician would come up with a way to find these primes in considerable less time as expected, it would mean the end of many encryption methods we know.

There are a few things to keep in mind about using GPG:

The secret key must be kept stored only on devices one trusts, and must not be handed out to anyone else. Remember, anyone with the secret key can decrypt your messages. Then again, you won’t be able to decrypt your messages when you lose your secret key. Note that the entire system breaks down when the end device (laptop, cell phone, etc) is compromised. You commonly store your secret key by encrypting it again with a password, but of course this won’t help when a keylogger is installed.

To prevent man-in-the-middle attacks, getting someones public key must go over a trusted channel. Otherwise, the man in the middle may sneak in a compromised public key allowing him to decrypt and encrypt the message while on the way to the real recipient. The analog way essentially involves meeting with somebody in person, checking that she/he is actually the person, and then handwrite the key down on a piece of paper. However in practice, one exchanges a fingerprint, which allows a unique lookup of the public key from a trusted key server (that is when the user has decided to store the public key on such a server). It is absolute necessary to have the correct fingerprint, as otherwise you may be getting the wrong “Edward Snowden” public key from the server. To get an idea of how paranoid it can get you may find it interesting to learn how Edward Snowden established contact with the Guardian journalists.

Tweeting your fingerprint is actually not such a bad idea either, as it is a relatively secure way of publishing your public key. The reason is that twitter uses secure http by default ensuring that your browser obtains the original tweet (i.e. you browser decrypts the tweet similar to the principle used in GPG), making it quite difficult to alter its content along the way. Below is an embedded tweet where I tweeted my GPG fingerprint. Note that this isn’t simply an image of a tweet (which potentially could have been modified by a man in the middle), but it is the javascript in your browser directly pulling the tweet from the twitter servers in a secure way. You can check that you got my actual tweet as the hyperlink on the date should get you to the original tweet (if you happen to land on a fake twitter account, or if it is only a simple image of a tweet, you have a good reason to start panicking)

Getting somewhat paranoid lately, here's my #gpg fingerprint CB56 8BCC 2F04 2DFE E166 2D9B A7DB DDEA FDE4 D78C

— Roelof Rietbroek (@r_rietje) February 1, 2017Keys which are signed by people you trust are less likely to be fake. Key owners have the possibility to sign each others key as an endorsement (I checked that this person is actually associated with this fingerprint), and upload the collected signatures to the public key servers. Have a look at the signatures on the public key of Richard Stallman for example. Some people take this so serious that they actually go to key signing parties, where fingerprints of the attendees are manually cross checked and subsequently signed. But for now, I can’t imagine scientists having key signing parties at scientific conferences.

You may not be able to read your messages with web-based email interfaces. Since the messages are stored as gibberish on the server, using the web interface of your email provider will show you, yes gibberish. After all your secret key should not be stored on that mail server, or on that internet-cafe terminal.

How to set up GPG for your devices

As you might have guessed, this post is not intended to give you a step by step guide to set up GPG on your device of choice, but more to make you aware of the possibilities, and sadly, the eventual necessity, of encrypting your email. However, I would like to point out a few links which may be consulted for setting things up. Note that there are usually more ways to accomplish this but below are a few common scenarios. They all use an underlying PGP tool with which you can manage your keys. This tool then communicates with your email client of choice out of the box or through a plugin.

Using thunderbird on linux, windows, or mac

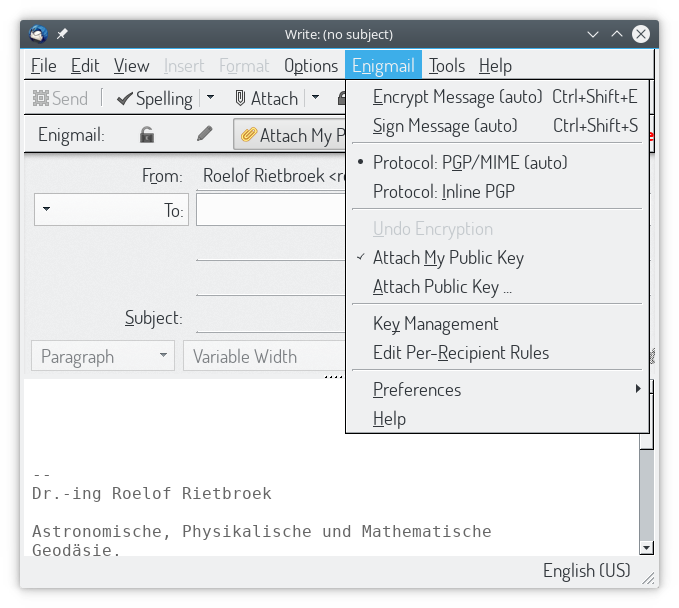

if you’re using thunderbird, there is a nifty plugin fittingly called Enigmail. Here’s a ‘quick start’ guide in setting this up for various OS’s. As mentioned before, it essentially consists of setting up GPG tool on your system, generating a key and using the plugin.

Using Enigmail in Thunderbird adds an enigmail menu item with several options to choose from

Using K-9 Mail with OpenKeychain on Android

There is a good email app called K-9 Mail which supports PGP encrypted messages when OpenKeychain is installed on your android device. Instructions can be found here.

Using Apples Mail with GPGtools

OK, I know lot of scientists like to work on Apple products, so I did some searching for you. It turns out that you can install a Mac port of GPG called GPGtools. This is supposed to integrate with Apples mail client ‘Mail’. Remarkably, GPGtools actually had to reverse engineer the Apple Mail software, as Apple does not provide official ways to write plugins for it. I leave it up to the reader what to think of this….

Using iOSMail with iPGMail

If you happen to own an apple phone too, you may want to try out iPGMail, which is supposed to integrate with iOSMail.

GPG as a digital vaccination program

As a final note, it is important to realize is that if you want to facilitate others to send encrypted mail, you have to offer them your public key, even if you consider the risk of being compromised yourself low. If scientists don’t bother to generate keys, it will become impossible to send GPG encrypted mails. So here’s an anology for you: convincing scientists to creating GPG keys is the digital equivalent of establishing a vaccination program…