Guess What: Sea Level Does Rise When You Melt Floating Ice

One may suspect that melting of floating ice would not cause a sea level change, but dissolving a chunk of the Larsen C ice shelf may actually change regional sea level by up to a meter.

The post was actually inspired by an email I received last week:

Subject: Remember Arquimedes before being silly

Dear Roelof,

The melting of the Artic ice sheets contributes ZERO to the sea level rise, simply because they are afloat, its basic hydrostatic!!!

A basic mistake and a shame to see these words coming from the mouth of a TUDelft graduate.

XXXXXXXX,

Naval Architect

Initially, I decided to ignore the email because of its tone, and obvious strawman argument. But, since the Archimedes argument has an interesting twist to it when ice melts in sea water, it was actually a good incentive to write a post on it. Furthermore, there are obviously still people today, who willfully or unwillfully, ignore the melting of grounded ice masses, while misinterpreting Archimedes’ principle in terms of volume instead of mass. So, I guess it doesn’t harm to reopen this case and use the dangling chunk of the Larsen C ice shelf as an example.

Misinterpreting Archimedes’ Principle

Having Archimedes in mind, one is inclined to reason that, when floating ice melts, the volume of sea water which it displaces will be perfectly compensated by the added volume from the melted ice. If this would be the case, then no net sea level will result from melting floating ice. However, Archimedes’ principle itself is formulated in terms of forces which are linked to weight (or equivalently mass) and not to volume:

Any object, wholly or partially immersed in a fluid, is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object

We will see that, in the case of melting ice in sea water, it certainly is not correct to assume a constant density throughout the melting process.

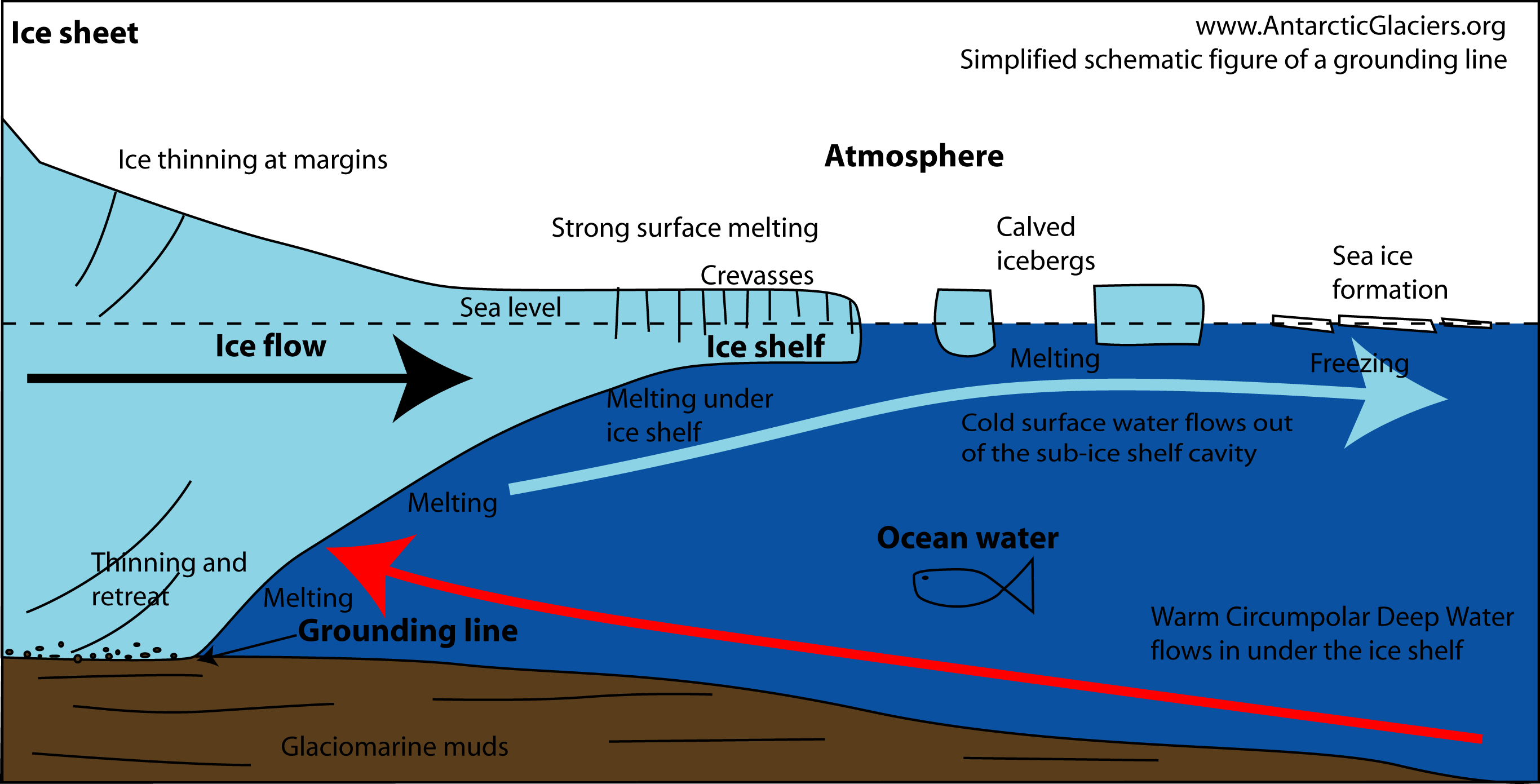

Grounded versus Floating Ice

A large part of the world's ice sheets are resting on the bedrock, compared to floating ice which either comes from the calving of glaciers or is formed at the surface during cold winter times.

To get an idea of all the factors at play here, one has to distinguish between ice which rests on the bedrock and ice which is afloat. The other issue, as discussed in this post, is that floating ice may induce regional changes in sea level when melted. I addressed these issues in the email reply, which I repeat here for completeness:

Dear XXXXXXX,

seeing that you took the effort to write me an email, and noticing that the topic obviously got you emotionally involved, I took the liberty to write you a quick response.

Just to set the record straight, you can not have heard me claiming that floating sea ice is driving sea level change, so I don’t understand where you got that idea.

Secondly, grounded (not floating) glaciers and ice sheets do contribute to sea level change. Besides the obvious Greenland ice sheet, the Arctic houses several islands which are home to grounded glaciers (e.g. Nova Zembla, Svalbard. etc), you only need to have a look at google earth to spot a few of those.

Thirdly, and here’s some food for thought, melting sea-ice may actually cause (small) changes in sea level. The salt concentration in ice bergs and sea -ice is less than that of the sea water which holds it buoyant. So if sea-ice melts in the water , the local salt concentration, and hence the sea water density, decreases. To maintain a constant pressure at the bottom of the ocean, which is a fine assumption when considering the surrounding waters to be unchanged, one would (regionally) need a higher column of less dense water. The Archimedes argument breaks down there because the density of the water obviously does not remain constant throughout the melting process. Density changes also occur when the temperature of the sea water changes due to the latent heat needed to convert ice to water, essentially counteracting (some of) the above effect. So regionally, melting of icebergs and sea-ice could in fact cause some sea level change. However, this effect is expected to be smaller than the direct contributions of the grounded ice sources.

You being a naval architect and former university employee, I trust you to be skeptical enough to reconsider your thoughts.

Kind regards,

Roelof Rietbroek

PS. In the future, please refrain from using patronizing language such as “Remember Arquimedes before being silly”, it does not impress me and it degrades an open discussion.

In retrospect, I apologize for the final sneer, a little patronizing by itself, but considering how the correspondence started of, it could have been worse.

In this post, I won’t go into detail on these grounded ice sheets, but these are indeed significant contributors to global sea level rise. It is the floating ice, which either has been calved of a glacier (i.e. ice bergs), or sea ice which may form at the ocean’s surface under wintery conditions, which will be in focus here.

Melting a piece of the Larsen C ice shelf

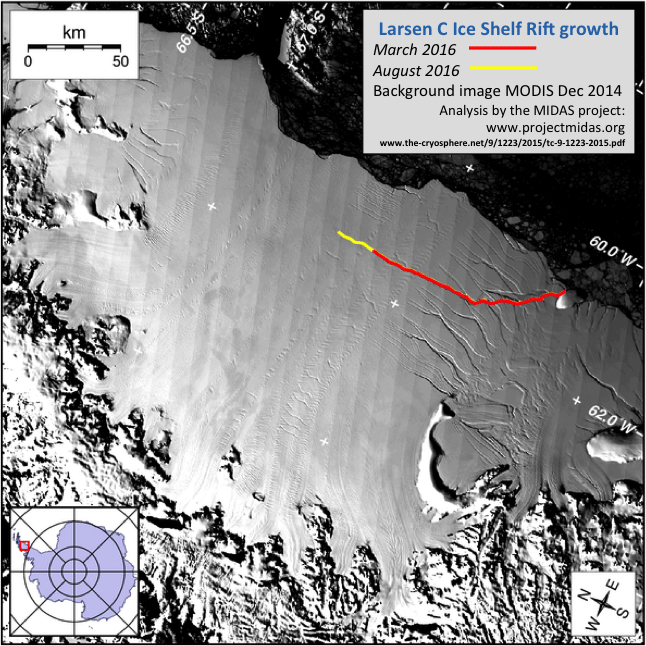

For some time now, scientist have been looking at a growing crack in the Larsen C ice shelf. The part which could potentially break off covers about 6000 km^2, which is about 1/7th of the Netherlands (e.g. the area of North and South Holland together).

Update 9 Jan 2017: Recently, the crack of the Larsen C has been growing quickly, and a break up is more likely in the near future.

A crack growing in the Larsen C ice sheet may lead to a significant piece breaking off

Using this as an extreme example, one could try to compute the sea surface height change after melting this chunk in a region of the ocean. In order to quantify this in a reasonable amount of time, we would need to make some design choices and simplifications. I implemented these in some matlab scripts which everyone interested can download and tinker with.

1 Define the Chunk of Ice

Based on some educated guesses the following chunk of the Larsen C shelf is to be melted:

- Surface area: 6000 sq. km

- Ice Thickness: 200 m

- ice density: 917 kg per cubic m

2 Define the pool of sea water to melt the ice in

Note that the pool of water must be large enough to facilitate the melting of the ice

- Surface area: 3 times the area of the ice shelf

- Depth of the affected water: 2000 m

- Initial in situ temperature: (allowed to vary from -2 to 22 deg. Celcius)

- Initial salt concentration: 34.5 practical salinity units

- Mean density of seawater: 1027 kg per cubic m

3 Make a monster slush Puppy from the Larsen C chunk

What I mean by this is that we conceptually disintegrate the ice shelf and distribute the ice evenly without melting. This step is needed as we want to let the melting affect the sea water evenly over the entire pool of water.

4 Compute the new temperature and salinity of the sea water after melting

Sea water and ice are really awkard substances, and respond non-linearly to temperature and salinity changes. To maintain thermodynamic consistency (i.e. conserve energy), I used software from the empirically determined Thermodynamic Equation Of Seawater (TEOS) to compute the sea water response (i.e. new temperature and salinity) to melting.

5 Integrate the density changes over the affected column to compute sea surface height change

Using the TEOS software again, we can now compute the density from the temperature and salinity profile before and after the melt event. These can than be numericaly intergrated over the entire water column to compute the sea surface height change.

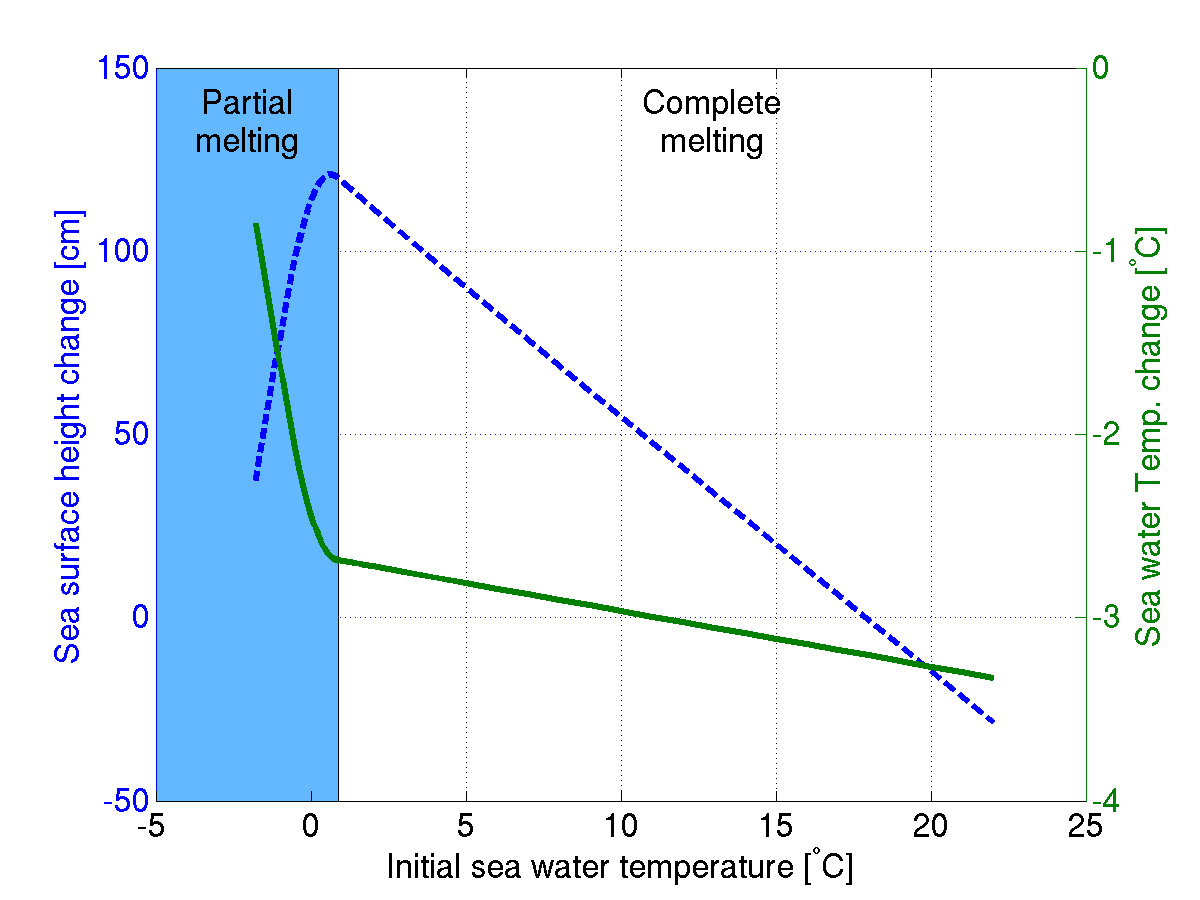

Melting the Larsen C chunk of ice may yield over 1 meter of regional sea level

Well, the result surprised me as well. I wasn’t expecting sea level changes over a meter. But then again, it is a gigantic piece of ice which has been melted here in a ‘relatively’ small area. The interesting thing is that the sea surface height change strongly depends on the initial temperature of the sea water. The plot below shows the dependency on the initial temperature of the sea water. And there are some interesting observations which can be made.

Regional sea level change (blue dashed line) when a 6000 sqkm floating chunk of the Larsen C ice shelf would be melted in a pool of sea water which is about 33 times the mass of the ice shelf itself. The blue area indicates the range of initial temperatures which didn't allow a complete melting of the ice. The green line indicates the drop in temperature of the sea water.

- Melting ice in colder waters cause a larger sea level rise. The maximum sea surface change (130 cm) occurs close to the point where the melting brings the sea water closest to its freezing temperature

- If you would tug the ice shelf to tropical waters (> 18 deg. C), the melting would actually cause a sea level drop.

- The temperature drop of the sea water increases when starting of with warmer waters.

To conclude, although floating ice is not expected to directly contribute much to global mean sea level rise, it’s contribution to regional sea level may be large enough to be detectable with sea surface height measurements such as those from for example radar altimetry.

It is worth noting that, even for global mean sea level rise, the volumetric changes due to melting of ice shelfs do cause a small net sea level rise. Shepherd et al. 2010 found a net contribution of 49 ± 8 microns per year, which is small compared to the currently observed global mean sea level rate of about 3 mm/yr.

The above experiment comes with it’s assumptions (e.g. no circulation and energy exchange with the surrounding waters), but can nevertheless be used as a conceptual model. Readers who find errors in the code are of course encouraged to report this.